Author: Sam Jacobs

A frozen cash value (FCV) life insurance policy is a form of private placement life insurance (PPLI) designed to fail some, but not all, of the tests to qualify as life insurance in the US. Specifically, an FCV policy violates Section 7702(b) by not meeting the cash value accumulation test and violates §7702(c) by failing the guideline premium test. The policy is neither a modified endowment contract (MEC) nor a non-MEC, and any cash value growth in the policy would be subject to taxation at ordinary rates.

However, FCV policies are treated as life insurance policies under §7702(g) if they meet the definition of life insurance in the jurisdiction where they're issued and have enough death benefit to be acceptable in the US, which is at least 5% of the policy's account value. If a §7702(g) compliant policy has a sufficient death benefit corridor, the death benefit is considered US tax compliant and can be received under §101(a) income tax-free.

FCV policies are usually issued from jurisdictions such as Bermuda, Cayman and Barbados, where the definition of life insurance is lower, typically requiring only a 1% amount of death benefit above the policy's account value. Issuing insurers in these countries raises the amount of risk to 5% or more on FCV policies to qualify for the death benefit to be compliant under §7702(g).

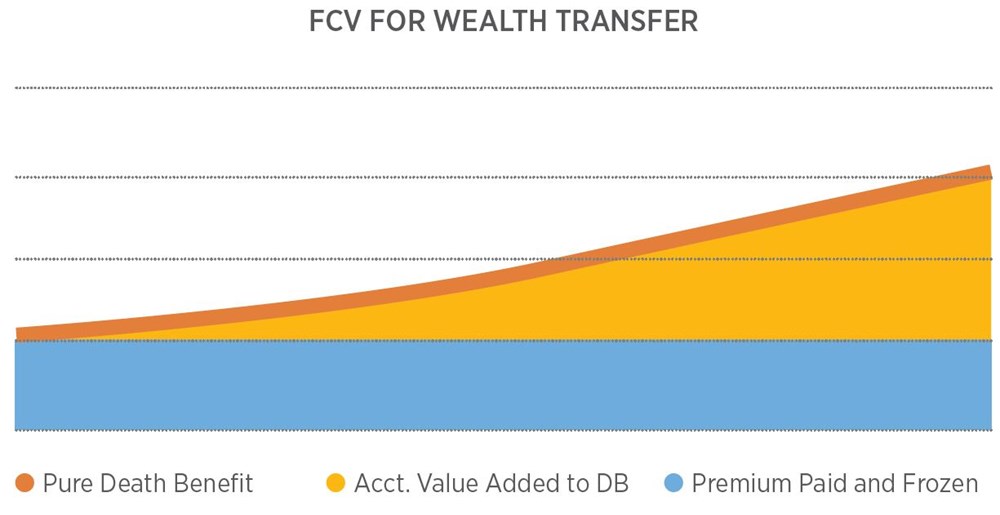

Structurally, premiums paid to an FCV policy are frozen, so that the cash value always equals the lesser of the premiums paid or the cash value, if investment losses reduce the cash value below the sum of the premiums paid. By freezing the cash value, growth that would be taxable under §7702(g) doesn't occur. Instead, the growth attributed to the increase in investment value is added to the 5% death benefit corridor and is received as a portion of the income-tax-free death benefit.

In the US, most states have anti-forfeiture laws that prevent a policyholder from forfeiting or forgoing upward cash value growth. Therefore, domestic life insurance companies don't issue FCV policies.

FCV policies can create tremendous tax-efficiency for:

- Transferring large amounts of wealth to beneficiaries

- Insureds with life insurance capacity limitations

- Foreigners planning to immigrate to the US

Private placement life insurance

As a form of PPLI, an FCV policy includes many of the same structural elements, benefits and rules pertaining to PPLI policies meeting the traditional definition of life insurance in the US, and that are issued as MEC or non-MEC policies. A policyholder should be a qualified purchaser and an accredited investor willing to accept the risks inherent in purchasing a variable insurance product without performance guarantees.

Investments within the policy should be in either an insurance dedicated fund (IDF) unavailable to the public or a separately managed account (SMA). Investments should meet §817(h) and Treasury regulation §1.817-5 diversification requirements, and the policyholder should not violate the Investor Control Doctrine as described in Webber vs. Commissioner (144 T.C. 17) 2015.

As with other PPLI policies, the life insurance company becomes the underlying beneficial owner of the investments held under an FCV policy. The investments are segregated and held separately from the general account assets of the insurer and aren't subject to the liabilities and creditors of the insurer.

*Clients may not dictate or control the IDF or SMA investments. Clients may transfer or re-locate among available investments.

Wealth transfer

Families wishing to transfer wealth intergenerationally find trust-owned FCVs a cost-effective tool to super-charge the amount of wealth to be transferred when compared to traditional life insurance policies. Since premiums paid into FCVs are frozen and all investment growth is added to the death benefit, the 5% amount of life insurance required above the account value results in an FCV policy with exceptionally low insurance costs, allowing the death benefit to grow more quickly than the death benefit of traditional policies.

For example, a $25 million investment in an FCV policy requiring a 5% corridor over the account value would necessitate $1.25 million of pure death benefit. The policy's initial $26.5 million income tax-free death benefit would be comprised of the account value of $25 million (made up of premiums paid) and investment growth, as well as the 5% required amount of death benefit risk over the account value provided by the insurer and its reinsurers. In contrast, a $25 million lump sum premium into a non-FCV policy would require a death benefit significantly more than the life insurance death benefit capacity of $100+/- million typically seen within the life insurance industry.

Due to the capacity constraints of fully complying with the US definition of life insurance, traditional policies can't achieve the same level of account value, greatly reducing the amount of death benefit and, thus, the amount of wealth that can be transferred income-tax and estate-tax free.

Insureds with life insurance capacity limitations

In the same way an FCV policy can boost the amount of wealth transferred because of the small amount of death benefit required to be compliant, the policy can similarly help insureds who have either exhausted most of their capacity or are assessed a higher cost of insurance due to health issues.

For example, the estate tax exemption will reach approximately $14 million per person by the time the current law sunsets at the end of 2025 and then reduce to approximately $7 million. Using a current exemption to fund traditional life insurance policies would require a very large death benefit and potentially eliminate additional capacity available in the marketplace. Given the small 5% amount of required life insurance, an FCV could provide capacity for additional sums to be converted to income tax-free death benefit.

Conversely, when the estate tax exemption falls, and the amount that can be gifted outside of an estate to an irrevocable trust is much smaller, an FCV policy's low-cost structure can provide more death benefit for the same premium as a non-FCV policy. This structure prevents having to use less tax-efficient methods to move money outside of the estate, such as private split dollar or various asset discounting strategies.

Life insurance companies routinely assess extra charges when calculating death benefit costs associated with current health findings and past health issues. When policies must have high death benefit corridors to be deemed a MEC or a non-MEC, these higher insurance costs can either neutralize the tax advantages of life insurance or result in an underwriter authorizing a smaller amount of capacity than desired. An FCV policy's low amount of death benefit can significantly mitigate these costs, while allowing the policyholder the ability to target the desired amount of coverage.

Foreigners planning to immigrate to the US

A common planning technique for those planning to move to the US is to transfer as much of their wealth as possible to an irrevocable trust ahead of becoming a US taxpayer. By doing so, the amount transferred isn't included in the immigrant's future US estate. A common technique to reduce or eliminate taxation at the high tax rates assessed by trusts is to either buy life insurance or an annuity.

As discussed, traditional life insurance policies have capacity limitations that restrict how much can be sheltered in these policies. While an unlimited amount of money could be placed into an annuity, the distributions from the annuity will be taxed at punishing trust rates, offsetting a good portion of the savings realized from the years of tax-deferral. An FCV solves both problems by requiring a small capacity for a large sum of premiums and the ability to pass on the accumulated value as part of an income tax-free death benefit while permitting the trustee to make tax-free withdrawals from the policy's basis, if needed.

Another pre-immigration planning problem an FCV policy solves is eliminating undistributed income (UNI) in foreign trusts with US beneficiaries. While an FCV policy doesn't eliminate existing UNI, it cuts off the growth of any additional UNI. Most foreign trusts are treated as foreign non-grantor trusts, which are only taxed on their US source income. The US Treasury imposes harsh taxation on UNI for US beneficiaries in the form of throwback rules.

Under the throwback rules, undistributed gains are taxed in the year of distribution to the beneficiary, including an additional compounded interest charge imposed on the UNI. The advantage of an FCV policy is significant, because premium contributions don't reduce the level of UNI within the trust but cut off the incremental growth of the problem. The cash value within the policy isn't considered trust income for trust accounting purposes and doesn't add to the UNI problem.

Further, tax-free withdrawals from the basis of an FCV policy aren't considered distributions that are subject to the throwback rules, and neither are the payments made to the US beneficiaries comprised from the income and estate tax-free death benefit.

The benefits of frozen cash value

Compounding: Compounding of investment income and gains is US federal income tax deferred.

Maximum tax efficiency: Subject to the exception for income on the contract, income and gains on the assets in the separate account generally aren't subject to US federal income tax as earned. Upon death of the insured, a US beneficiary can receive the entire death benefit free of US federal income tax.

Asset management free of US tax considerations: Because income and gains on segregated account assets aren't currently taxable to the policyholder or the beneficiary, the segregated account is managed more efficiently based on solely economic factors (which may include withholding taxes charged to the segregated account from source countries, including the US).

Access to non-US investment funds: US persons investing directly in non-US investment funds are often subject to adverse US federal income tax rules. Non-US investment funds may be held in segregated accounts without those tax rules applying to the policyholder.

High limit of premium payments: Because an FCV permits a 5% net amount at risk, the total premium is only limited by the insurer's capacity to provide for that amount at risk.

Access to securities: As a non-US person, the insurer may invest in securities not registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that may be inaccessible directly by an individual US investor.

Limited mortality costs: Mortality costs are relatively low, because the true risk component of the death benefit is limited to a percentage of the cash surrender value.

Flexibility: While the policyholder can't personally manage the segregated account assets, the policyholder can designate an investment manager and make a general allocation of the investment assets by designating broad investment guidelines. The policyholder can replace the investment manager or revise the asset allocations from time to time.

Rules of the road

Two nuances to owning an FCV policy are important to note.

First, a policyholder should pay particular attention to how the pure costs of insurance are paid. These costs can either be paid from the basis in the policy or from a source outside of the policy. Unlike non-FCV policies where insurance costs are deducted from the cash value growth, there's technically no cash value growth within an FCV policy. Therefore, if funds from the growth of the premiums paid were used to pay insurance costs, these amounts would be deemed as non-compliant cash value growth and taxable to the policyholder at ordinary rates.

Another benefit to paying the cost of insurance from outside of the policy is that the expense load on the investment growth is substantially eliminated, allowing growth to occur unencumbered by the insurance costs, unlike non-FCV policies.

The second nuance a policyholder must be aware of is that, if they surrender an FCV policy, they're only entitled to receive the lesser of premiums paid or the cash value. All investment gains would be forfeited to the life insurance company. Conceptually, this is because cash value growth cannot technically occur with FCV policies without being subject to taxation at ordinary rates.

Over the years, a few insurance companies issuing FCV policies have asserted that if a policyholder were to make up for all back taxes due on the investment growth, they should be able to receive the investment gains when surrendering the policy. Today, the industry is largely aligned with the reasoning that such a provision presents a substance-over-form concern, whereby an argument that an FCV policy never existed in the first place if such accommodations to reach the investment growth are in place from the beginning.

Seek assistance

An FCV solution is appealing for wealthy individuals with excess after-tax funds seeking tax-free compounding of income and gains and who have no expected need to access appreciation above the total premium paid during their lifetimes. Contact a Gallagher consultant today to learn how our tailored solutions can be a valuable tool for your needs and how to effectively implement this strategy.